How colonialist depictions of Palestinians feed western ideas of eastern ‘barbarism’

Elizabeth Vibert, University of Victoria

Like so many other Palestinians, my friend Abeer Salah (not her real name) lives in exile. For Salah, home is Baqa’a refugee camp 20 kilometres north of Jordan’s capital of Amman. But she has family and friends trapped in Gaza. Since the horrific Hamas attacks of Oct. 7 and Israel’s catastrophic military action in Gaza, she has been watching the news and social media closely.

Recently, Salah shared a video clip of Israel’s ambassador to the United Nations, Gilad Erdan, holding up a brick to show how “terrorist” Palestinians throw them at soldiers and settlers. The clip, recorded last year, has been circulating again.

To my friend, this clip illustrates how western governments and media have long tended to depict Palestinians as backward and prone to violence.

“This man is trying to show that Palestinians are a barbaric people,” Salah said. “They defend their land and their people with stones. They’re backward. Meanwhile, Israelis have tanks.”

As a historian who studies colonial pasts I understand what Salah is saying. The dismissal of Palestinians as “barbaric” or somehow less human is rooted in a long history of colonizing narratives, including views of Indigenous lands and peoples as “uncivilized.”

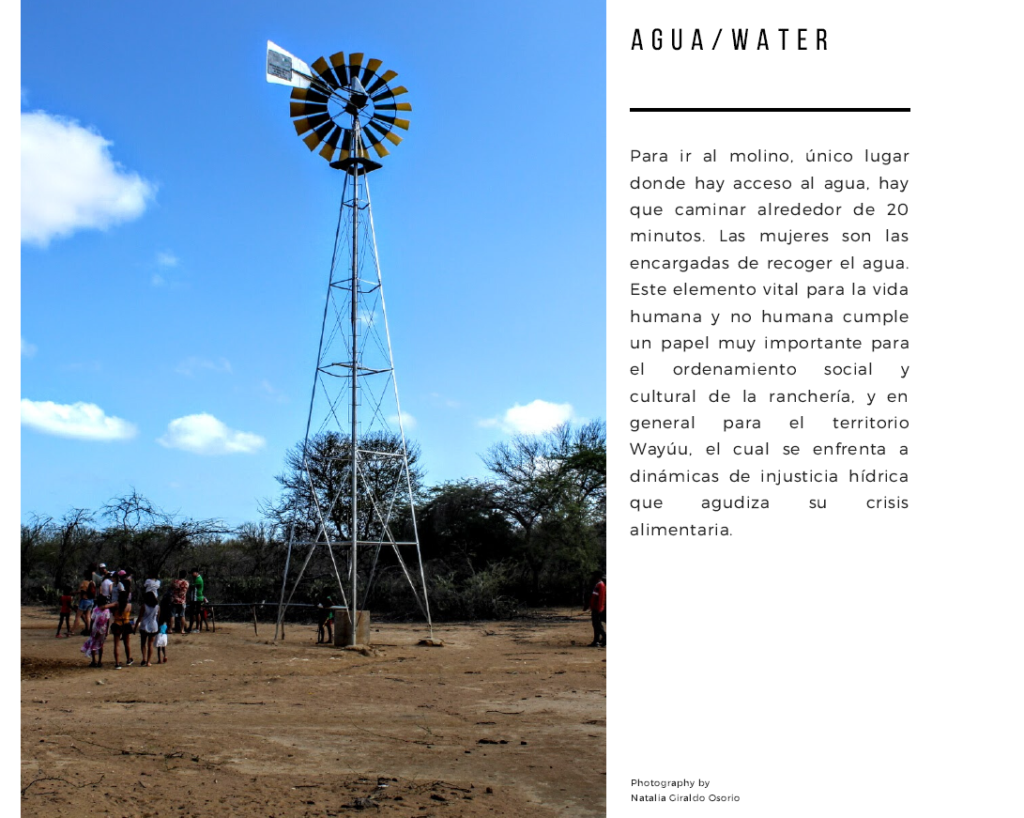

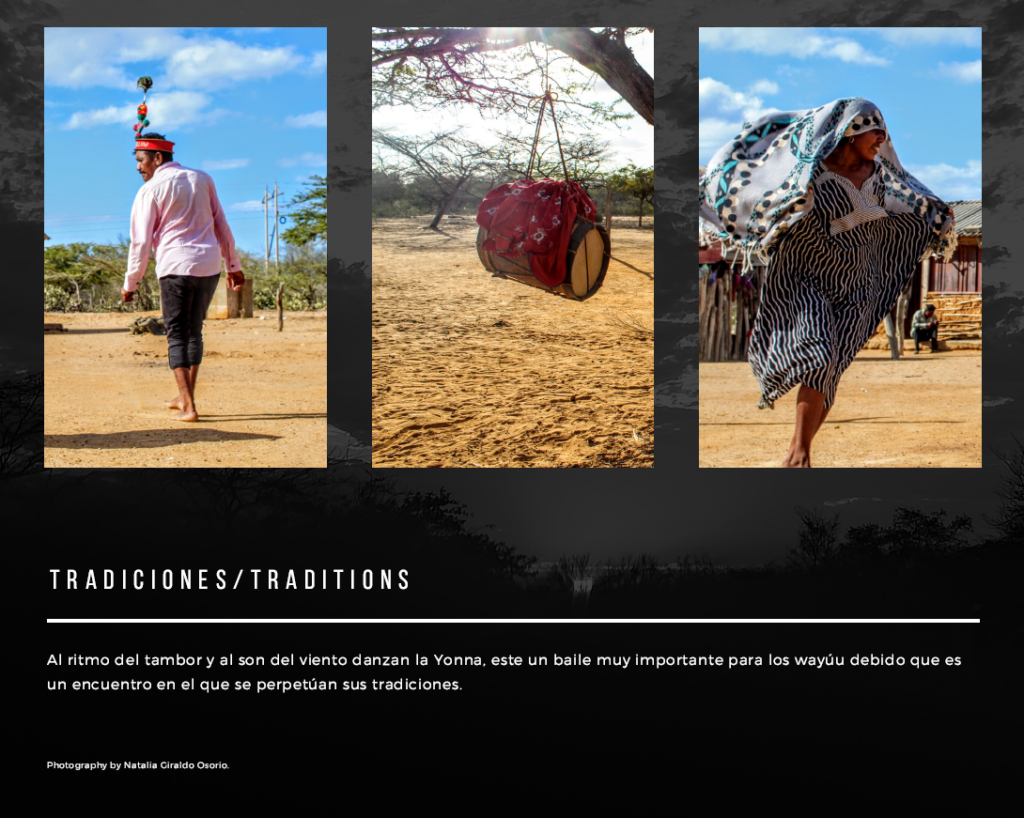

For the past five years, I have been working on an oral history research project and documentary film with Palestinian refugees in Baqa’a Camp. The film, made by a team including consulting producer Salam Barakat Guenette, explores how families and communities keep their food culture alive in exile. It offers a striking counter narrative to the stereotypes often levelled at Palestinians.

Colonial claims: ‘savage’ and ‘barbaric’

In his classic 1978 book Orientalism, Palestinian-American literary scholar Edward Said explained how British colonizers wielded the “power to narrate” as they cast their eyes, administrators and armies across the lands of “the East.”

Said, whose study focused on depictions of West Asia and North Africa (Europe’s “Middle East”), showed how the “absolute demarcation between East and West” was centuries in the making. By the 18th century, the binary of East versus West or “us” versus “them” had grown into a vast archive of western-produced “knowledge.” The relationship was cemented in the West as “superior” versus “inferior,” “civilized” versus “uncivilized,” “rational” versus “depraved” in all arenas of life: politics, culture, religion.

Psychologists and biologists have shown that “us” versus “them” binaries may be a nearly universal human impulse. Such binaries become consequential when they harden into pernicious and violent racism, and are used to justify the taking of land, homes, food systems, water and lives.

Classifying societies by ‘stages’ of civilization

By the mid-1700s, the great thinkers of the Enlightenment in Scotland, England and France were fine-tuning “four stages” theories to classify human societies according to imagined “stages of civilization.”

In most such schemes, hunting-gathering was placed at the bottom (“savage”) stage, followed by pastoralism (shepherding etc., often labeled “barbarism”), agriculture (emerging “civilization”), and at the apex, European commercial society. Unsurprisingly, Enlightenment writers placed themselves at the “apex.”

People inhabiting lands sought for colonization were often described as “wasting” land, having “backward” food production practices and being in need of “civilization” — all according to western definitions.

Beginning in the late 19th century, Zionists who initiated the nationalist project for Israel, in a land both peoples considered their ancestral home, gave little thought to the Palestinians. Zionists were deeply informed by scornful views of small-scale farming and sheep-herding societies. And British administrators during the Mandate period (1920-1948) took a similarly dim view of much Arab agriculture.

‘A land without a people’

Palestinians were resisting colonial designs on their lands even before the British issued the infamous Balfour Declaration of 1917 — a document that in a short paragraph promised Jewish people a “national home” in Palestine, so long as they did nothing to “prejudice the civil and religious rights of the existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine.”

This was breathtakingly dehumanizing language for the “existing non-Jewish communities” — the Palestinian Muslims and Christians who were then more than 90 per cent of the population. Historian Rashid Khalidi argues that Palestinians viewed the Balfour Declaration as “a proclamation of war on them.” It marked the start of “a century-long colonial conflict in Palestine,” a conflict in which Britain, the United States and other outside powers have played key roles.

Zionist leaders’ claims about “a land without a people for a people without a land”, then, fit within a larger narrative that erased Palestinians and dismissed traditional Palestinian stewardship of the land.

The Zionist project to “make the desert bloom” was based, in part, on damaging misunderstandings of Arab dryland wheat and baʿlī farming systems. Baʿlī planting, tillage and plant protection methods, as demonstrated by Palestinian geographer Omar Tesdell, facilitate growing crops without irrigation. These agro-ecological practices are at once resilient and dynamic, and have much to teach farmers in increasingly drought-prone regions.

Intense threats to land

For years, farmers in the Palestinian territories have faced intense threats to their land and livelihoods. For instance, farms and gardens in Gaza, adapted across generations to challenging local conditions, were often targeted in military operations. In the midst of Israel’s catastrophic air and ground war on Gaza’s people, it is hard to conceive of a future for their local food systems.

In the West Bank, Israel’s eight-metre-high separation wall and encroaching Jewish settlements have systematically cut off many Palestinian farmers from their olive groves and other lands. With all eyes now on Gaza, settler violence on Palestinian lands has intensified.

As we have seen throughout history, dehumanization can have tragic and devastating impacts on people and land. Nearly half a century ago Edward Said asked a poignant question: Can we continue to divide humans into stark categories of “us” versus “them” and survive the consequences humanely? ![]()

Elizabeth Vibert, Professor of Colonial History, University of Victoria

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.