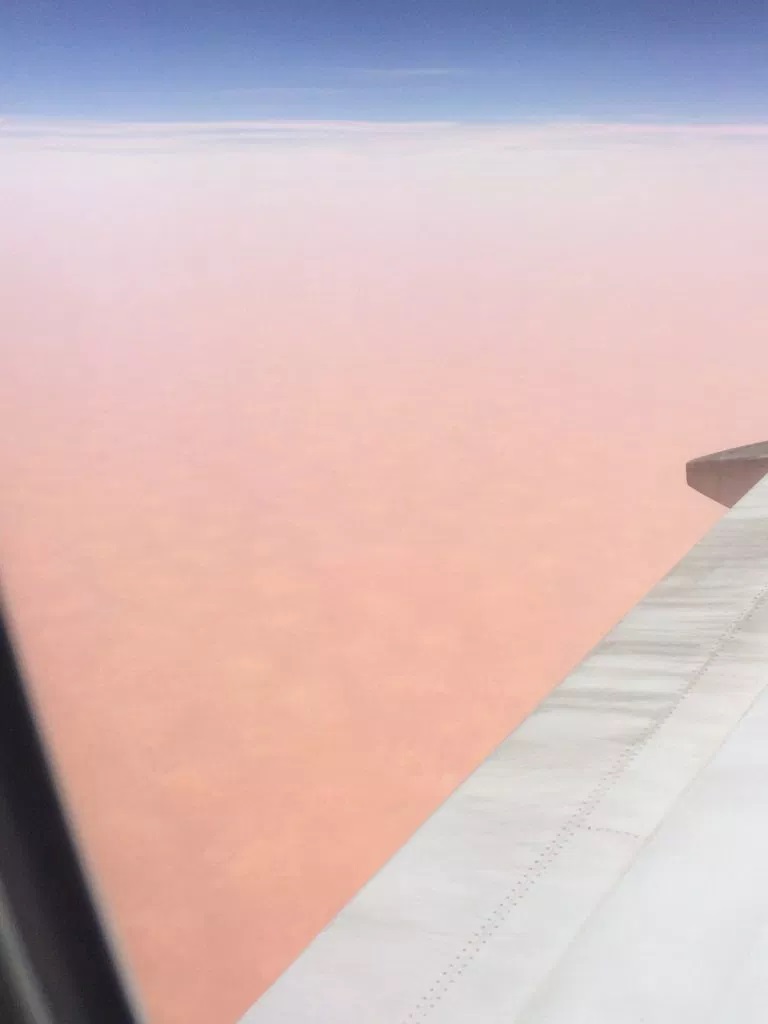

It takes hours to fly across the Sahara Desert. I strained my neck taking photos, trying to capture the unearthly colour on my phone. I didn’t manage but I did get some images that glow a strange golden pink. I fell asleep, tired from the effort of staring awkwardly over my shoulder. When I woke we had left the desert and entered the zone of mottled browns and greens. The flight-tracking map showed the place name ‘Maiduguri’ off the tip of the right wing. Maiduguri. Site of seemingly endless brutal attacks, massive human displacement, and thousands of deaths at the hands of Boko Haram terrorists in the past few years. There have been many times more casualties of terrorism in this corner of Nigeria in three years than in the entire West since 9/11. Yet most people in the West have never heard of Maiduguri. Why should we? There’s quite enough hardship closer to home – enough poverty and homelessness and senseless violence (at the hands of intimate partners if not armed terrorists) to keep our heads spinning. Why spare a thought for Maiduguri?

Because it’s dangerous not to. I don’t mean dangerous in practical terms, as in ‘if we don’t combat the causes of terrorism (among them desperate poverty and hopelessness), instability will fuel more terror and the terrorists will pitch up at our place.’ This seems so obvious as to not need stating. And besides, that ship has sailed. I’m talking about the moral danger of turning inward. If we focus all our attention on our little patch – our body as our temple, our family or our city as our world – we diminish our connection to something bigger. When we lose sight of our connection to humanity it becomes all too easy to think of people out there as beyond our concern. Them, not us; certainly not equal. How do we decide where is ‘out there’? Is it on another continent? On an Indigenous reserve? Next thing we're building walls around our homes, if we haven’t already.

I’m not proposing we all get on a plane to Africa. Heading off to faraway places doesn’t inoculate against ‘othering’ habits of thought. In fact going to places where people do things differently can confirm prejudices in minds that are narrowed by intolerance (or worse, by blind certainty of their own rightness). But if it isn’t necessary to go to Maiduguri, it is necessary to think beyond the local. We need to inform ourselves, question what’s going on so that we’re reminded, at least occasionally, that there is a world of human struggle, conflict, love, and beauty out there. That struggle is connected to our own in all sorts of ways – through histories of colonialism, self-serving trade policies, destabilizing global politics – but most intimately through our common humanity.