The T'Sou-ke First Nation

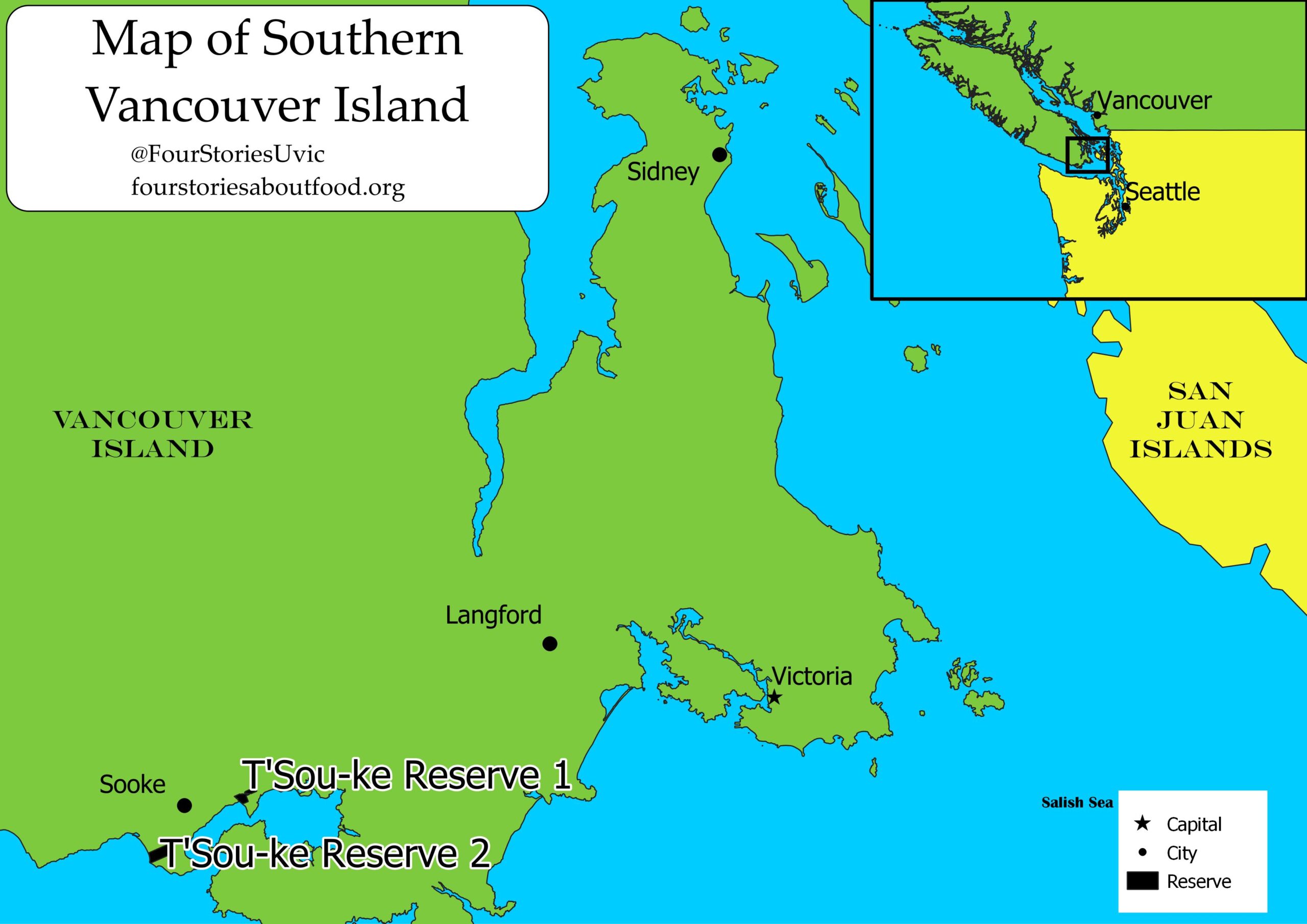

The Indigenous community of T’Sou-ke First Nation is located on Vancouver Island’s southern coast, in British Columbia, Canada. Historically, Coast Salish communities in the Pacific Northwest, including T’Sou-ke First Nation, had some of the highest population densities on the North American continent because of the abundance of resources in the land and the water (Olson & Steager, 2015). On May 1 1850, under the Douglas Treaty, T’Sou-ke received forty-eight pounds, six shillings, eight pence and fifty-two blankets for all of their land, except for sixty-eight hectares, which comprise the community’s two current day reserves (Olson & Steager, 2015). The community’s coerced displacement from their traditional lands and limited access to food sources completely disrupted T’Sou-ke First Nation’s traditional food system.

Despite a history of tremendous loss, T’Sou-ke First Nation is an inspiration of resilience, working towards sustainable programming and sovereignty in a number of areas. In 2008, T’Sou-ke undertook a large project to create a vision for the community which all members were committed to. Through this process they identified four pillars: energy autonomy, cultural renaissance, economic development and Food Security. After completing this process, T’Sou-ke began building a solar intensive community (Moore, 2013). The national and international recognition T’Sou-ke Nation has received, with regards to their tremendous success in solar energy, reflects the power of Indigenous ways of knowing.

In terms of Food Sovereignty efforts, T’Sou-ke First Nation has a community garden and greenhouse that supports some of the community’s food needs; produce is used for a biweekly needs-based meals-on-wheels program, Elder wellness days and nature walks, as well as the weekly community luncheons and culture nights (Ladybug Garden & Greenhouse, 2018). Additionally, the community holds a range of workshops, gatherings and hikes, providing opportunities for members to engage with traditional foods such as blackberries, camas potatoes and seafood. Kuhnlein (2014) identified the importance of efforts to re-establish the utilization of traditional and sustainable food practices as central to revitalizing Indigenous identity due to the integral relationship between the health of the land and the health of Indigenous peoples; this finding reinforces the importance of projects such as the Ladybug Garden & Greenhouse.

Impacts of the climate crisis have been identified by community members, specifically the impacts of the forestry industry and changing climate. Practices of clear cutting and overharvesting have destroyed the community’s two largest berry fields (Poirier, 2020). Harvesting trees prematurely impacts the entire forest ecosystem, which the community views as a food forest rather than a commodity to be sold. Additionally, community members who are primarily responsible for the growing of foods at the garden as well as the harvesting of wild foods have noticed that native food sources are not as successful as even five years ago. Plants will flower and then they don’t bear fruit; if they do produce fruit it is often airy, lacking moisture and seeds; a lack of seeds means that no new plants will grow the following year. Community members have expressed that they are very concerned for the future of these native plants because they will eventually become extinct if they are no longer able to replenish themselves (Poirier, 2020).

T’Sou-ke First Nation’s Chief and Council acknowledges the impact of bringing together Indigenous communities from all over the world to strengthen knowledge and share in ideas for a sustainable future (G. Planes, personal communication, January 10 2020). Learning from others is an important source of growing for the community, and the hope is that the Four Stories About Food Sovereignty project will provide an opportunity to further progress towards sovereignty goals. The community hopes to generate environmental, cultural and community development through their involvement in this project.

References

Kuhnlein, H. (2014). Food system sustainability for health and well-being of Indigenous Peoples. Public Health Nutrition, 18(13), 2415-2424. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/s1368980014002961

Ladybug Garden & Greenhouse. (2018). T’Sou-ke Nation. Retrieved 15 February 2020, from http://www.tsoukenation.com/ladybug-garden-greenhouse/

Moore, A. (2013). Power to the People: T’Sou-ke Nation’s Community Energy Solutions. Sooke, BC

Olson, R., & Steager, T. (2015). T'Sou-ke Nation: Traditional Marine Resource

Knowledge and Use Study Report. Victoria: The Firelight Group.

Planes, G. (2020, January 10). Personal interview.

Poirier, B. (2020). From The Ocean Floor To The Mountain Top: Using The Renewable Energy Of Mother Earth To Grow Food. Retrieved from University of Guelph Atrium.